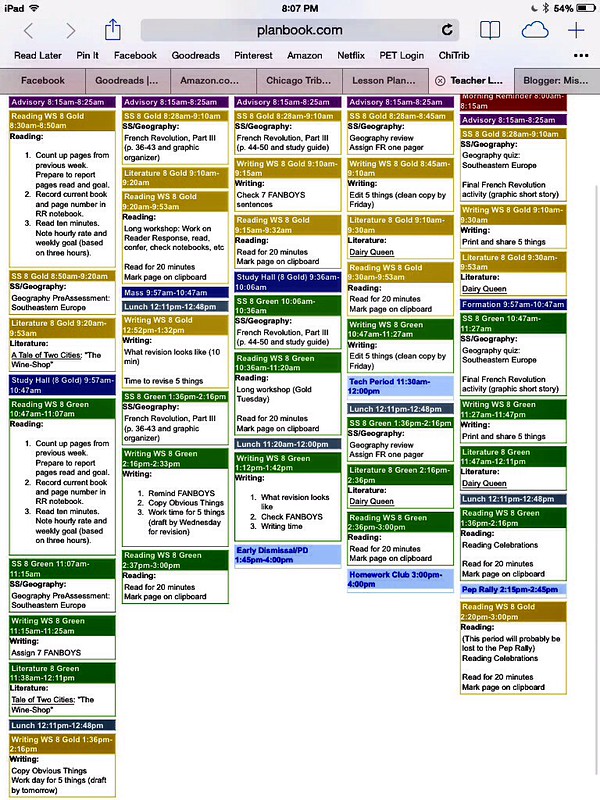

Here are my plans for this week:

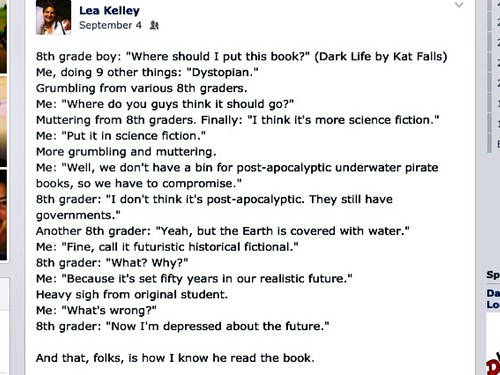

I have been wondering if I am trying to do too much with my 8th graders. One challenge of teaching humanities instead of a single subject is that it is largely up to me to balance the subjects within the thirteen periods each week that I teach each section. The plan above represents my attempt to balance the sheer number of minutes that I spend on each area, even if I inevitably end up adjusting the times. (The above schedule doesn't fully convey the number of interruptions that this particular week will have, for example.)

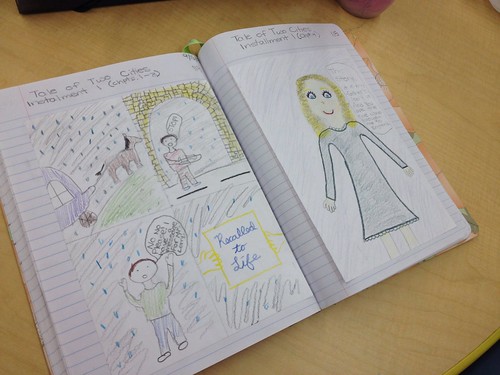

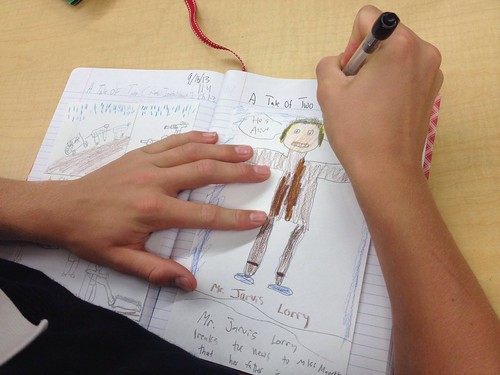

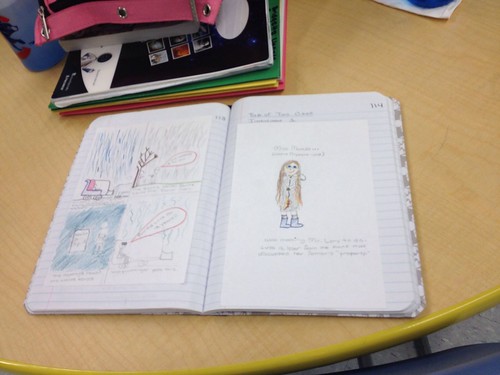

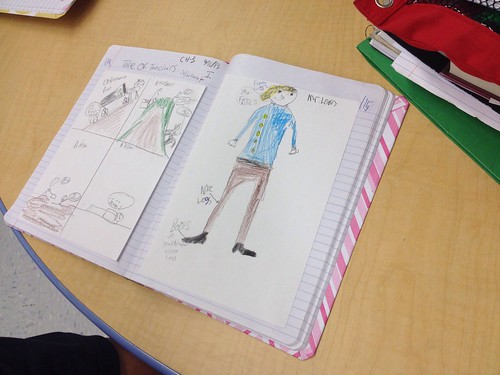

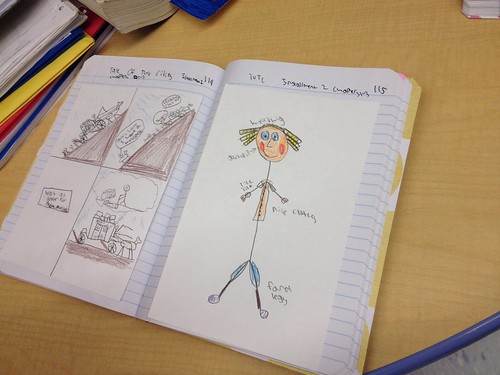

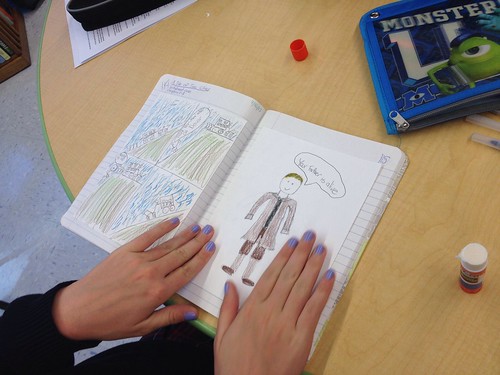

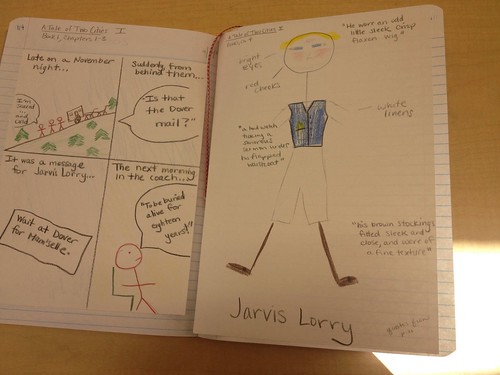

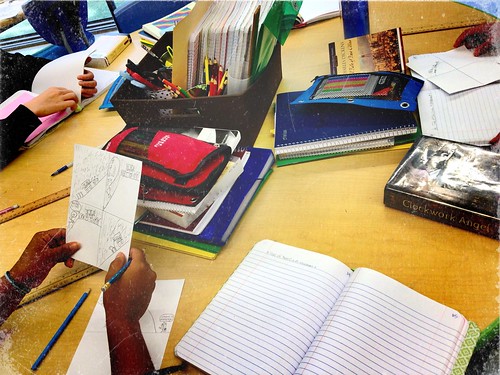

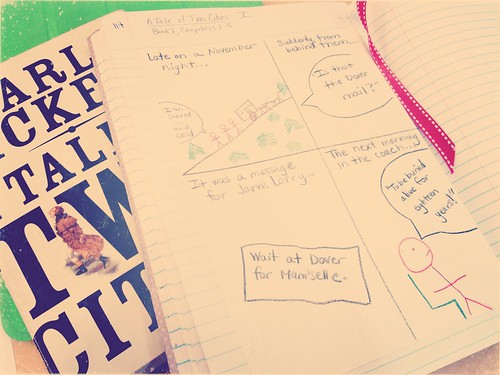

This week we are primarily wrapping up some work and continuing some longer projects. We'll finish our study of the French Revolution this week, and I would like the students to write a short reflection about what they learned. I also need to know about their experience with the text and its accompanying materials so that I can plan our next unit. We'll need to keep our French Revolution knowledge close enough that we can access it when we get to that point in A Tale of Two Cities. We're on chapter 5 in that book, and students will draw another 4-panel graphic adaptation for their notebooks, along with their standing assignment of one independent reading reader response and next week's chapter of TOTC.

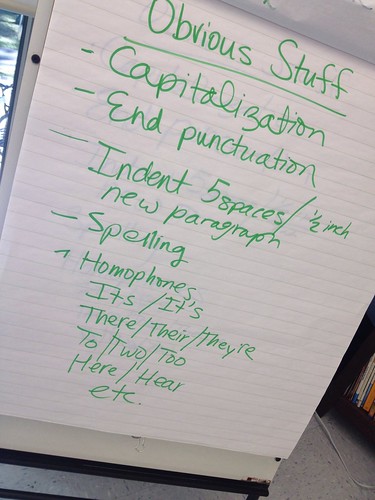

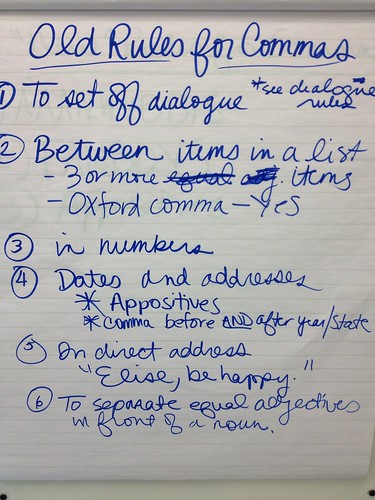

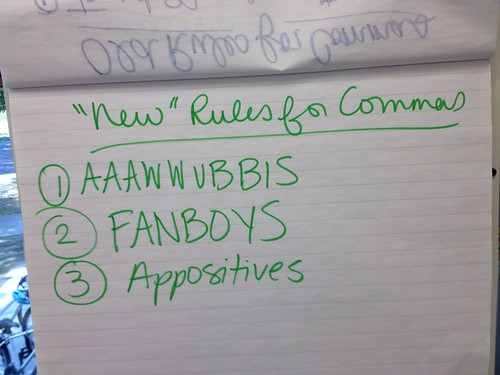

We need to pick up the pace in writing. Writing workshop is getting bumped around by the schedule, and I need to reconsider when I schedule it. On the other hand, our work in reading and history gives us even more to write about, so perhaps it is right for writing to begin to pick up now. I have students who are ready for fancy grammar, and students who need more time with less fancy concepts. I need time to meet with both groups.

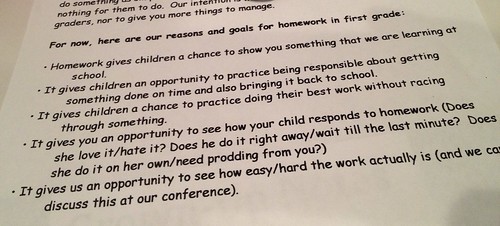

Yet as I worked on the above plans yesterday, and scheduled the accompanying assignments in edmodo, I wondered if I was overdoing it. Fourteen assignments in one week, even if almost all of it happens in class? How much is too much?